No New Categories

In college, I took a self-defense class, taught by Sensei Flagg. The next semester, I took a kickboxing class, taught by Sensei Flagg. The next and final semester, I took an Isshin-Ryū Karate class, taught by Sensei Flagg.

It was the exact same class each time. The administrators just couldn’t decide how to categorize it.

According to the school’s policy, retakes did not provide additional credits or grades. But when I noticed the administration’s constant category changes of the same karate class, I realized it would count for a new credit and grade each time. So I kept enrolling and boosted my grades and course-credit total.

This category shuffle had a minor effect on my overall grade (and belt ranking). In the business of software, however, companies live or die by the category they compete in. It affects the number of potential buyers, their budgets, their perceived value of the product, and the alternatives they compare against the product. It even affects how much interest the company can garner from investors and job candidates.

Some think product categories have a loophole similar to my college karate classes: Instead of slugging it out in an existing category, just create a new one! Instead of extra credits, the thinking goes, you become the default market leader and get millions in revenue from the many buyers who realize they can’t live without this kind of product.

On top of that, startup founders are told that legends such as Steve Jobs, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, and Marc Benioff succeeded because they created categories instead of disrupting old ones.

An exploitable loophole. Growth and revenue. The secret behind the success of legends. No wonder so many founders wonder whether they should create a new category.

From helping startups since 2013 and analyzing tech IPOs from the past two years, I’ve reached this surprising conclusion:

You don’t need a new category. In fact, the vast majority of startups succeed in an existing category. As did, it turns out, Steve Jobs, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, and Marc Benioff.

The smartphone category existed over a decade before Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone. Although Salesforce was one of the first breakthrough Software-as-a-Service companies, its founder Marc Benioff neither coined nor used the term “SaaS,” which really emerged in a 2001 industry publication (more on that below). Larry Page and Sergey Brin created an innovative method of ranking web sites but always called Google a “search engine.”

And if you do try it, category creation is much harder and costlier than it seems.

This article summarizes my perspective on the matter, based on extensive research and actual go-to-market experiences — some of which are included here as anecdotal stories — and makes the case that startups are more likely to succeed by competing in an existing category than by trying to create a new one.

Categories Are Just Words

A category (“market category” or “product category”) is a group of products that solve a similar problem, in a similar way, to a similar audience. Examples in software include Application Performance Monitoring (APM), Marketing Platforms, and Platforms as a Service (PaaS).

But really, categories are just words.

There’s no single authority that decides what is or isn’t a word, or their meaning. A word is real if enough people use it and it means what most people think it means. Some words change meaning; some disappear; new ones emerge; everything is fluid. And so with categories.

Changes happen as a result of significant innovations, shifts in buyer perceptions or needs, economic environments, and many other factors. Whatever the cause, the change first spreads in the wild before being documented and standardized by some influential person or organization.

As one analyst from the research firm Gartner told me:

“When we either create or advance terms that we’re hearing, it’s always to provide clarity to the market.”

For example, in 2001, the Software & Information Industry Association introduced the world to SaaS: “Software as a Service (SaaS), commonly referred to as the Application Service Provider (ASP) model, is heralded by many as the new wave in application software distribution.” Salesforce, which launched two years prior and uniquely provided its software through the cloud, influenced this change, but it did not coin the term.

None of this diminishes the power of categories. In addition to meaning, they also carry associations, expectations, and perceptions. They can even evoke emotions.

Take NoSQL, for instance. If you’re familiar with databases, that label might stir expectations such as “open-source” and “distributed”; product associations such as DynamoDB, Cassandra, and MongoDB; and perceptions such as “risk of data loss,” “fad,” or “best choice for big data.” Depending on your experience with databases or the year in which you read this, you may involuntarily feel either glee or disgust.

Such reactions have tremendous implications for the company behind the product. The category with which buyers associate that product impacts their level of interest, what they compare it against, how much they expect and are willing to pay, what they expect the product to do, and so on. Companies can influence — but not control — the category they’re associated with through positioning.

Positioning is the deliberate effort to make a product or service be associated with a specific category for some advantage. Everything from the way the product is built to the way it’s packaged, priced, sold, and marketed can be a part of that effort.

For example, Redis makes a database that fits the NoSQL definition, but maybe they prefer not to be associated with “cheap” and “fad,” nor to compete with the many NoSQL solutions in the market. So they consistently label the product as an “in-memory database” and avoid mentionioning NoSQL throughout the corporate or open-source sites. (This is speculation for illustrative purposes.)

Although successful positioning could make a significant impact for a startup, it takes work to figure out how and where to position the product to maximize returns. What’s more, any category with a sizable market is sure to already include competition from market leaders or a swarm of other startups.

Which is why some startups attempt a shortcut with category creation.

Category creation is a marketing strategy in which a company designs a new product category — along with name, problems, solutions, and audience — and promotes that category alongside the product itself. The goal is to convince buyers they need a certain kind of product, then win that growing market by virtue of having the only (or leading) product in it.

The idea of hacking your way to market dominance and unicorn status is understandably alluring to startup founders. If you could mold the market in your favor and sidestep the incumbents and startup competition, why wouldn’t you?

Because, as it turns out, category creation is neither a shortcut nor a surefire way to succeed.

Category Creation Is Not a Shortcut

Category creation is much harder and costlier than it seems — in time, energy, resources, and opportunity cost.

The hard part isn’t coming up with the strategy. The hard part is moving the market — the buyers and their purchasing behavior — with you to the new category. Until then, you’re not a king; you’re just the mayor of a one-person town.

In other words, everyone can be “#1” in their own category, but that isn’t enough.

This requirement to move the market is badly and consistently underestimated by startups considering this strategy. It is underestimated in part because it is unacknowledged by proponents of category creation, who say much about “category kings” and market dominance but not enough about the time and cost it takes to get there, nor about the many companies that tried and failed to build a market around their new category.

What does it take to move the market? Marketing. So launching a product and category together just doubles the effort, resources, and time required for sales and marketing. Instead of helping explain the product, the new category just creates another thing that needs explaining.

The cost may be even worse than that, because new categories face more resistance from buyers than new products. As one research study explains:

“Owing to their vested interest in constructing and conveying the value of a new category in the market, producers’ discursive attempts at category-creation are liable to be discounted and viewed with suspicion by other constituents, especially consumers, in a market.” (Durand & Khaire, 2016)

In the worst case, it can be repulsive. Buyers might feel they’re being sold buzzwords and snake oil. This is a big risk for startups selling to technical audiences who are already sensitive to anything that smells like marketing.

Launching a category at the same time as bringing a product to market is like trying to bring two products to market. Companies like Monday.com, HubSpot, and Fastly can afford to take shots at creating new categories — Work OS, Flywheel Model, and Edge Cloud Platform, respectively — because they have the resources and cash runway to see it through, just as they would with a new product or major release. Those who don’t have the resources to launch two products at the same time also don’t have the resources to successfully launch a product and a category at the same time.

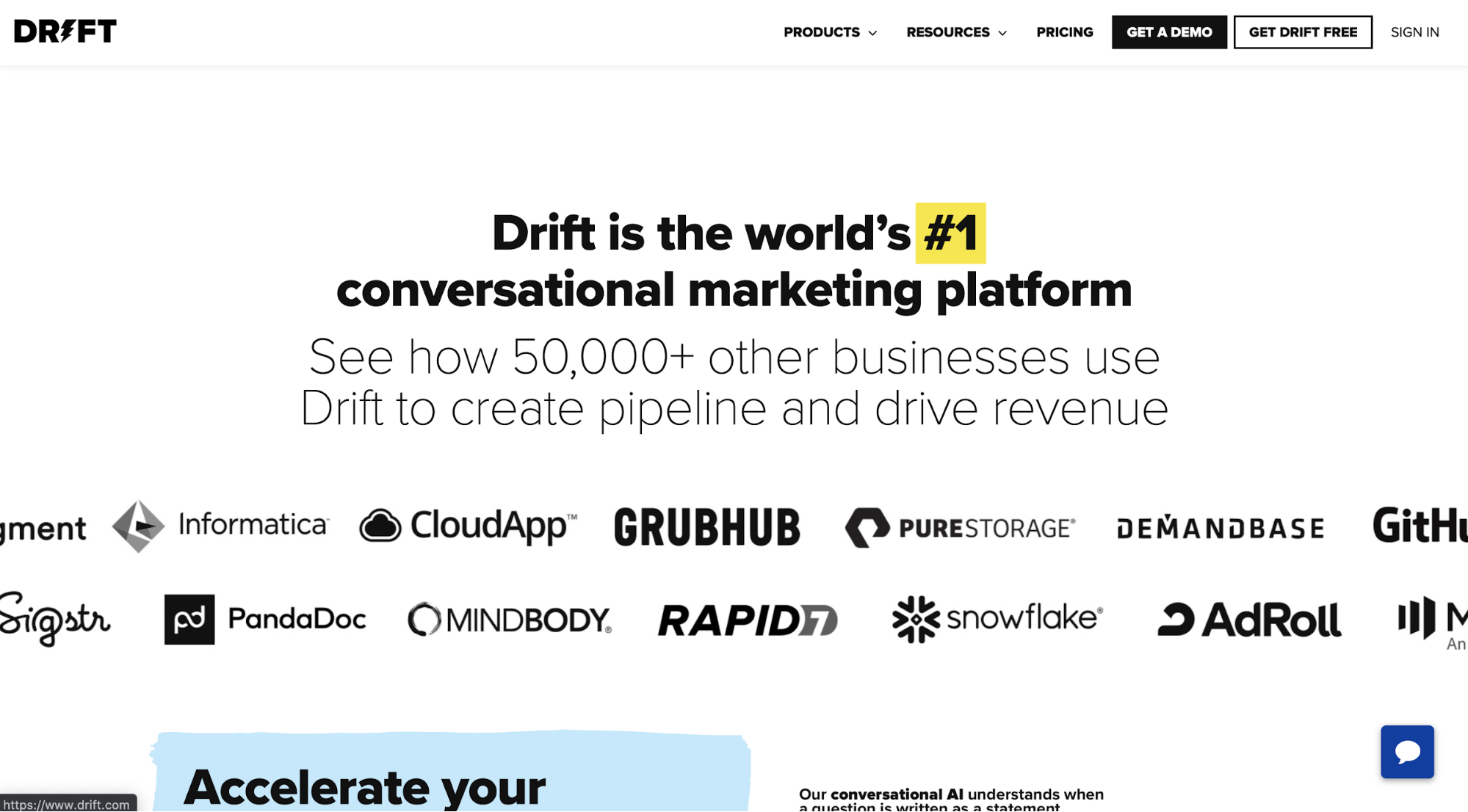

Story: Drift

As part of the go-to-market strategy for their live-chat product, Drift created the category of Conversational Marketing.

Everything was aligned in their favor, and they did it about as well as anyone could: David Cancel, the Founder and CEO, was the Chief Product Officer at HubSpot for three years; they raised $107M from legendary investors like Sequoia; they wrote a book on marketing; they started and grew a podcast show; they built a large team of talented marketers; they’ve been doing this consistently for years; and their buyers — marketers — are extremely amenable to marketing.

And yet:

- They are still competing uphill against other live chat solutions.

- They are left out of the conversation when it comes to the broader Conversational Platform and Conversational AI categories.

- Unlike Inbound Marketing and Account Based Marketing (ABM), the category Conversational Marketing is still not in the daily vocabulary of marketers and executives.

- Their growth is owed largely to marketing and not product innovation, which means their position in the market is far from secured.

- They must still rely on conventional product labels (“live chat,” “video,” “email,” “automation”) and conventional value propositions (“build more pipeline, increase close rates, and retain customers”) to attract and convert buyers.

- Just days before publication of this article, Drift revealed they have given up on Conversational Marketing and launched a second attempt at category creation (“Revenue Acceleration Platform”).

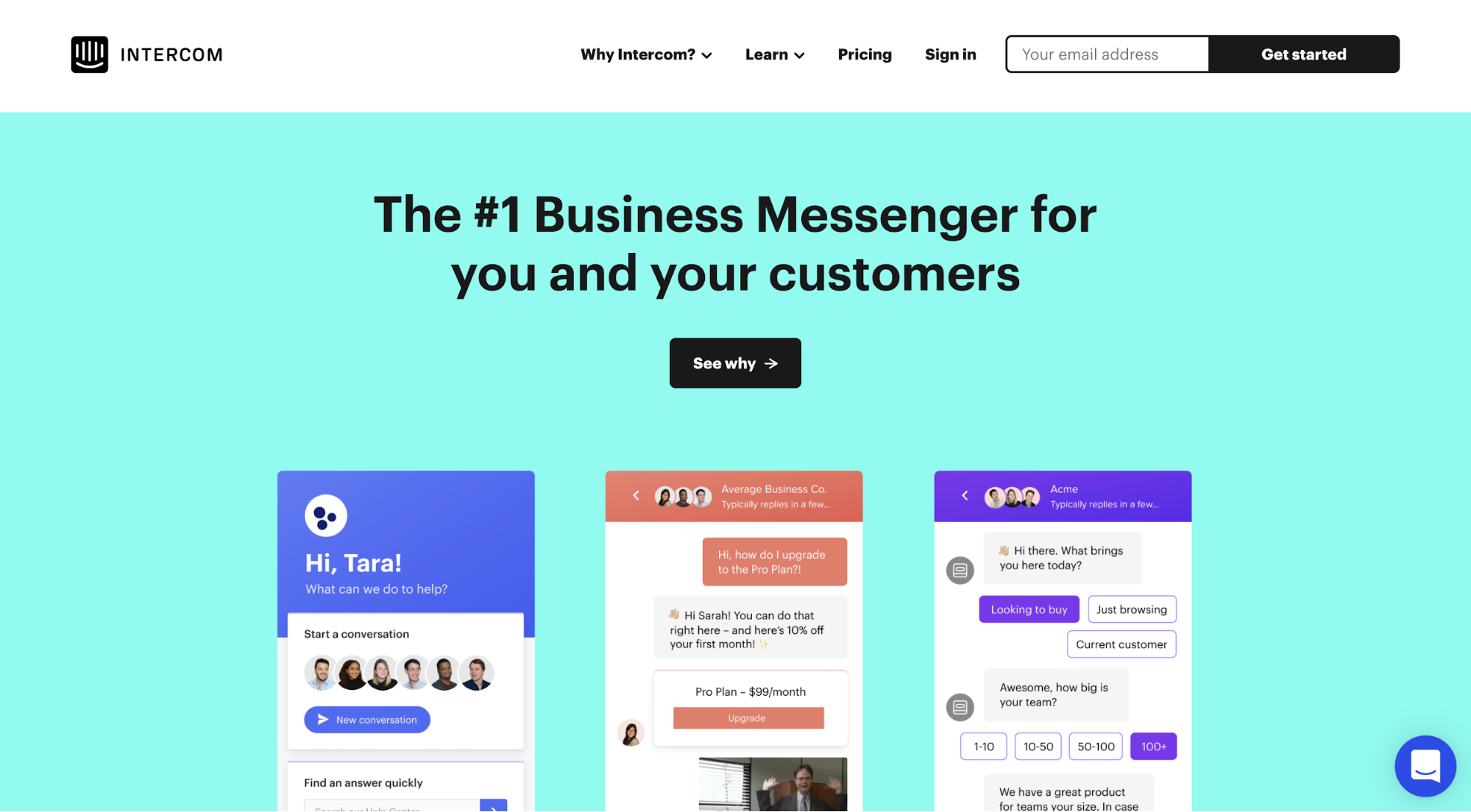

Story: Netlify

Netlify spent many years and resources promoting the Jamstack category of development tools. In some respects, it has been very successful: They’re unanimously credited with coining the term, they’re the company most associated with the label, there’s an entire ecosystem of Jamstack solutions, and they now have a million users. Despite all that, they still had challenges in attracting and converting large customers.

In 2018, Netlify asked me to figure out what would make large companies pay for their enterprise plans. I found five things, and being “the No. 1 Jamstack platform” was not one of them. What we found helped inform the messaging, positioning, packaging, and pricing overhaul that followed soon after, which you can now see throughout their site. Notice “Jamstack” isn’t mentioned until the very bottom of the homepage.

In the end, Netlify was able to successfully move up market and meet aggressive growth goals. What it took to get there, however, was the same messaging and positioning work that every startup needs. It’s not clear how much the multi-year category creation effort helped compared to just, say, competing as a Platform as a Service (PaaS) — still the category of choice on their LinkedIn profile.

Story: D2iQ

D2iQ, formerly Mesosphere, put all their chips on creating the Day 2 Operations category, going so far as renaming the company — the D2 is for Day 2 — in August 2019. One year later, the company’s future looks gloomy, and the “day2ops” category label is hardly mentioned in the market.

A director of engineering at a public tech company, whom I interviewed as part of a customer research project, has never heard of the term. Another engineering leader scoffed when asked and dismissed it as a marketing buzzword. Although it’s an unfortunate outcome for D2iQ, for everyone else, it’s a lesson that “category creation” is not a miracle cure, and can fail even with enormous resources behind it.

(Note: Days before publication of this article, D2iQ started to back away from the Day 2 Operations category and toward something more conventional. Their headline was switched from “A Smarter Approach to Day 2 Operations” to “The Leading Independent Kubernetes Platform.” This makes it the second startup to give up on category creation before I could complete this article.)

The hard truth is that companies can pour every last dollar, drop of sweat, and moment of time into category creation and still fail to move the market.

The takeaway is not that Drift, Netlify, or D2iQ are doing anything wrong. It’s that the category creation strategy is much harder than it seems and comes at a large cost of time and resources to even attempt. That’s time and resources that could be spent on product innovation and winning over an existing market.

These examples raise the question: Did these companies even need to bother trying to create a category?

Most Successful Startups Did Not Create Categories

Two misconceptions may lead founders to believe that category creation is the best or only go-to-market strategy, even if it does come at a significant cost. The first is that category creation was the secret behind successful and legendary startups. The second is that there’s no way to succeed in an existing category that already has a market leader.

If both were true, we’d expect most successful startups to be positioning their products in unique and original categories. Do they?

New Categories Among Recent IPOs

The first misconception — that creating a category is often the key to success — exists because many articles about category creation use the term as a synonym for “innovation.” Here is a typical example from an article promoting category creation as a strategy:

“Jobs’ greatest genius was his ability to invent three new categories: the digital music player, the smartphone and the tablet.”

Steve Jobs did not create the smartphone, MP3 player, or tablet categories. All three existed before the iPhone, iPod, and iPad. What he did was launch innovative products into existing categories, which were incredibly successful and eventually changed the behavior of consumers and competitors. Those are perfect examples of organic category shifts.

Looking back at a few standout companies and attributing some key to their success does not reliably tell us what’s likely to work for others in the future. A recent, unfiltered sample set would provide a better indicator of what’s likely to work or not. Say, for example, a list of B2B software companies that went public in 2018 and 2019.

In 2019, there were 14 B2B software companies that went public. All but two of them marketed their products in existing categories, rather than something unique:

| Company | Self-Assigned Label in April 2018 | Unique Category? |

|---|---|---|

| Fastly | Edge Cloud Platform | Yes |

| PagerDuty | Digital Operations Management | Yes |

| Cambium Networks | Fixed Wireless Backhaul and Access Solutions | No |

| Change Healthcare | Healthcare Technology & Business Solutions | No |

| Cloudflare | Web Performance & Security Company | No |

| CrowdStrike Holdings | Cloud-Delivered Endpoint Protection | No |

| Datadog | Modern Monitoring & Analytics | No |

| Dynatrace | Digital Performance and application performance monitoring (APM) | No |

| Health Catalyst | Healthcare Analytics and Data Warehousing | No |

| Livongo | Digital Health Management | No |

| Medallia | Enterprise Customer Experience Management Platform | No |

| Phreesia | Customized Patient Intake Software | No |

| Slack (enterprise) | Collaboration Hub | No |

| Zoom | Video Conferencing and Web Conferencing Service | No |

B2B tech companies that went public in 2019, and the category promoted on their homepage the year before IPO.

For the two exceptions in the list, it’s difficult to know how much the unique categories helped them, and at what cost. Before PagerDuty launched the Digital Operations Management category in 2016, they tried “Incident Management Platform” in 2015, and “Operations Performance Management” before that. Fastly already raised a total of $179M and reached a $650M valuation before switching their marketed category from Content Delivery Network (CDN) to the unique Edge Cloud Platform in 2017.

The other 12 companies on the list opted to disrupt an established category (such as Zoom: Video Conferencing) or to lead an emerging category (such as Medallia: Customer Experience Management) instead of trying something new.

The proportion was similar in 2018, with 10 out of 11 companies competing in established, non-unique categories the year before going public:

| Company | Self-Assigned Label in May 2017 | Unique Category? |

|---|---|---|

| Anaplan | Connected Planning | Yes |

| Dropbox | File Sharing and Storage | No |

| Tenable | Vulnerability Management | No |

| Domo | Business Intelligence | No |

| Avalara | Tax Automation | No |

| Smartsheet | Work Management and Automation | No |

| Docusign | Electronic Signatures | No |

| Pivotal Software | Agile development | No |

| Zuora | Subscription Billing, Commerce & Finance Solutions | No |

| Carbon Black | Endpoint Protection | No |

| Zscaler | Cloud Security | No |

B2B tech companies that went public in 2018, and the category promoted on their homepage the year before IPO.

The takeaway from the past two years of IPOs: The majority (88%) of B2B startups reach the IPO milestone by marketing themselves within existing categories, not in categories they created. Although these companies will certainly contribute to the evolution of their respective categories, they’re not trying to carve out new categories of their own.

Multiple Winners Within Categories

In a 2014 article, Kevin Maney, co-author of a book promoting category creation, makes the kind of statement that leads to the misconception that there’s no way to succeed in an existing category that already has a market leader, implying startups may as well try to create a new category:

“Even worse news for the second-tier companies: The study found that a six-year-old startup that isn’t yet a Category King has almost zero chance of becoming one. Hundreds of companies are left to forever survive, like raccoons at a summer camp, on their category’s scraps. That explains why Uber was valued at $41 billion earlier this month, while at about the same time the No. 2 in that space, Lyft, was valued about 40 times lower, at $1.2 billion. The rest of that category is barely noticeable. Investors look at the future value of that category and see one company taking most of it.”

“The [study] puts some data behind the provocative advice investor Peter Thiel doles out in his book and lectures. Competition is for losers, he likes to say. The goal of any startup is to become a monopoly in its space. In the tech business, you’re either a 1 or a 0, and in a given market there’s only one 1. Everyone else winds up with a tax write-off and some coffee mugs with an extinct logo.”

While this is great pep talk for the boardroom of a moonshot startup, it has little other practical use.

Lyft, with a market cap of $8.8B at the time of writing, is not complaining despite being second in the market. Neither is Pepsi, which also sits at No. 2 and owns 25% of a multi-billion-dollar market. There are multiple marketing platforms that are successful by any measure, all happily competing in that category: Hubspot has a market cap of $7B, Marketo was acquired for $4.75B by Adobe, and Mailchimp was last valued at $4.2B.

As for the idea of an unmovable king, history is full of former category leaders who thought the same thing (Snap, Yahoo, IBM, Palm, Compaq, AltaVista, and MySpace, just to name a few). The shifting nature of markets and the accelerating pace of innovation means the top position is always up for grabs.

Now knowing that category creation is neither a shortcut nor a necessity to succeed, what can startups do instead?

Enter Established or Emerging Categories

Imagine how early explorers felt when they discovered trade winds. They were able to go faster and farther just by getting into the right “lane” and keeping the ship pointed in the right direction. This by no means guaranteed a safe voyage, but it helped.

Positioning products into an existing market is like finding a trade wind. It doesn’t guarantee success, but it helps startups:

- Focus their time, effort, and resources on marketing and selling the product itself rather than the category. Prospective buyers (and investors, and job candidates) familiar with the category will already have the necessary background context.

- Find prospective buyers who are already using, evaluating, or learning about solutions in the category (for example, by advertising for search terms related to the category or by reaching out to known users of competing products in the category).

- Better convey the product’s value, because there are other solutions in the category to compare against.

- Predict their sales and marketing performance, revenue, growth, and challenges by analyzing other companies in that category.

- Choose from a plethora of category labels instead of trying to come up with something clever and hoping it sticks.

Existing categories can be split into “established” and “emerging” to distinguish between those with high present potential from those with high future potential.

Disrupt an Established Category

Established categories are over five years old and have broad awareness in the market, with many large companies competing within them. Examples include Video Conferencing, DevOps, CRM, Project Management, and Security Information and Event Management (SIEM).

Entering an established market with an innovative product has high present potential because there is already a well-informed audience primed to pay for solutions. Buyers in established categories already:

- Understand their challenges and their magnitude. They don’t need convincing about having a painful problem.

- Use a product in this space and know its limitations and downsides all too well.

- Have budget allocation for a product or multiple products in this category.

- Know about alternative solutions and the benefits and limitations of each.

- Tried or considered building a solution in house and understand the maintenance burden that comes with that.

- Designed systems and workflows around this type of solution, making it a critical part of their organization.

- Have buy-in from their colleagues and other stakeholders to use this type of solution.

- Know where to look for reliable information about the category and its products.

All this makes it relatively easy for a startup with an innovative product to start attracting and converting enterprise buyers. Startups can study the existing market to identify where buyers get their information, what they search for, what pains they experience with current or available options, what other solutions cost, what marketing strategies and tactics are working for other companies, and so on, and set the go-to-market strategy accordingly.

Since the software industry changes rapidly, there’s a risk that the established category will shift dramatically or go away entirely, requiring the startup to overhaul their go-to-market strategy or, at the very least, update their messaging.

Join an Emerging Category

Emerging categories are less than five years old and have very limited but growing awareness among buyers, definitions and expectations that are still being formed, and mostly startups (along with the most agile of large companies) competing within them. Examples include Managed Kubernetes, Low-Code, No-Code, Observability, AIOps, Zero Trust, and ModelOps.

Joining an emerging category provides valuable opportunities to:

- Become the go-to, trusted, and popular source of information about the emerging topic, attracting buyers as they grow in numbers.

- Set or at least affect the associations, expectations, and buying criteria among buyers in the market in a way that maps well with the startup’s product but creates barriers to entry for competitors — such as pricing model and range, expected integrations, which features come standard and which are premium, ease of use, installation experience, and so on.

- Secure early partnerships with companies in adjacent categories and convert their customers.

- Grab significant portions of the market with relatively few resources, before large competitors swoop in with unlimited resources.

- Leverage the hype around the category to get recognition and mentions from press and analysts.

- Attract greater investor and job-candidate interest by virtue of working in a new and cutting-edge space.

All of this creates the potential for rapid and sustained growth as the market expands.

Unfortunately, there is also uncertainty about how big the market will actually get, along with the added challenge of educating potential buyers about a new class of solutions and their value. These challenges, however, are not nearly as difficult as those of attempting to unilaterally create a new category.

(Recall that new categories are typically coined by influential people or organizations who recognize shifts in the market and document it, and it happens to stick. Case in point: Both the Zero Trust and Low-Code emerging categories were coined by analysts at Forrester. ModelOps emerged around 2018 with no clear origin as far as I know — even if it was a software vendor that coined the term, they’re not reaping any competitive advantage for doing so.)

Story: Teleport

When the team behind Teleport brought me in to help figure out what messaging would attract and convert enterprise buyers to their innovative product, they hadn’t made any decisions about positioning. They just went with the first idea which was to label it as a “modern SSH.” (SSH is a common method of accessing remote servers, and “modern” is a bad word for describing software products.)

The problem was that enterprise buyers — such as VPs of Engineering and CTOs — weren’t looking for a “modern” way to do SSH. Even if they stumbled upon Teleport, seeing “SSH” made them think of OpenSSH, an open-source alternative. As a result, the team spent a large part of every sales demo explaining how Teleport and OpenSSH are different, and why one should pay for the former when the latter is free.

In figuring out how to describe the product in a compelling way, we first determined what would make enterprise buyers want to pay for the product — their desired outcomes. Once we had those, we discovered there’s already an established category of products that solves those same outcomes: Privileged Access Management (PAM).

This category had several large, legacy incumbents like Cyberark ($4.7B market cap) and Centrify ($115M revenue in 2019), which meant there were many educated buyers eager for an innovative alternative and primed to pay for enterprise-level plans.

We came up with messaging to describe Teleport in a way that positions it as a high-value, innovative alternative to those legacy PAM solutions. (Tagline: “Privileged Access Management that doesn’t get in the way.”) Within six months of launching the new messaging, revenue shot up by more than 600%, and sales velocity — the speed at which new deals are won — significantly increased, too.

The team learned a valuable lesson: It pays to position innovative products into established markets. They then applied that lesson to Teleport when Zero Trust became an emerging category (“Zero Trust security that doesn’t get in the way”), and again when COVID-19 made remote access a top priority for many enterprises (“Remote access that doesn’t get in the way”).

Story: Domino Data Lab

When Domino Data Lab went to market in 2014, they entered the emerging Data Science Platform category. Few understood what it meant. People were just learning what “data science” was, as a practice, and whether they should hire “data scientists.” Nonetheless, it was a real category that was talked about by analysts and startups.

Other startups such as Y-hat, Sense, and Datascience.com were popping up and helping to educate the market on this new thing called a “data science platform.” This allowed Domino to dedicate their resources and energy to customer acquisition and product development to meet demand exactly as the demand was growing.

When the Domino founders brought me in in 2015, we put our attention toward attracting and converting enterprise buyers already interested in data science tooling, rather than pushing the new category.

We figured out where awareness and demand for data science platforms were growing the fastest, and went there. For instance, one of Domino’s first enterprise clients, Allstate, provided a clue: the insurance industry. So we put Domino squarely in the field of vision of insurance companies. We produced an insurance-focused case study and promoted it on LinkedIn to anyone technical or analytical at an insurance company (there weren’t many people calling themselves data scientists at the time). This campaign became one of the top sources of inbound sales leads, and helped Domino take a large chunk of the insurance market. We then took this approach for the financial-services and life-sciences industries, which to this day make up a meaningful portion of revenue for Domino.

Thanks to their sustained focus on innovating within an emerging category, by the time I finished consulting Domino in 2020, their platform was being used in 20% of all Fortune 100 companies.

There is a lesson there, in both flexibility and hedging bets.

Test Categories Before Committing

Whether choosing to create a category or enter an existing one, consider testing it first by marketing one product (out of a product lineup) or by running a limited campaign to promote the product within that category. This allows for seeing and measuring how well (or not) the new positioning attracts and converts the target buyers with much less risk and up-front costs.

For example:

With the emergence of the ModelOps category, Domino is testing the waters by releasing a standalone product to compete in that category.

Centrify is wading into Zero Trust while keeping one foot in their older category, Privileged Access Management, in which they raised $94 million in funding and were acquired for an undisclosed amount.

Netlify kept one foot in the established Static Site Hosting category for the entirety of their effort to grow the Jamstack category, thus keeping a steady flow of new users during that time.

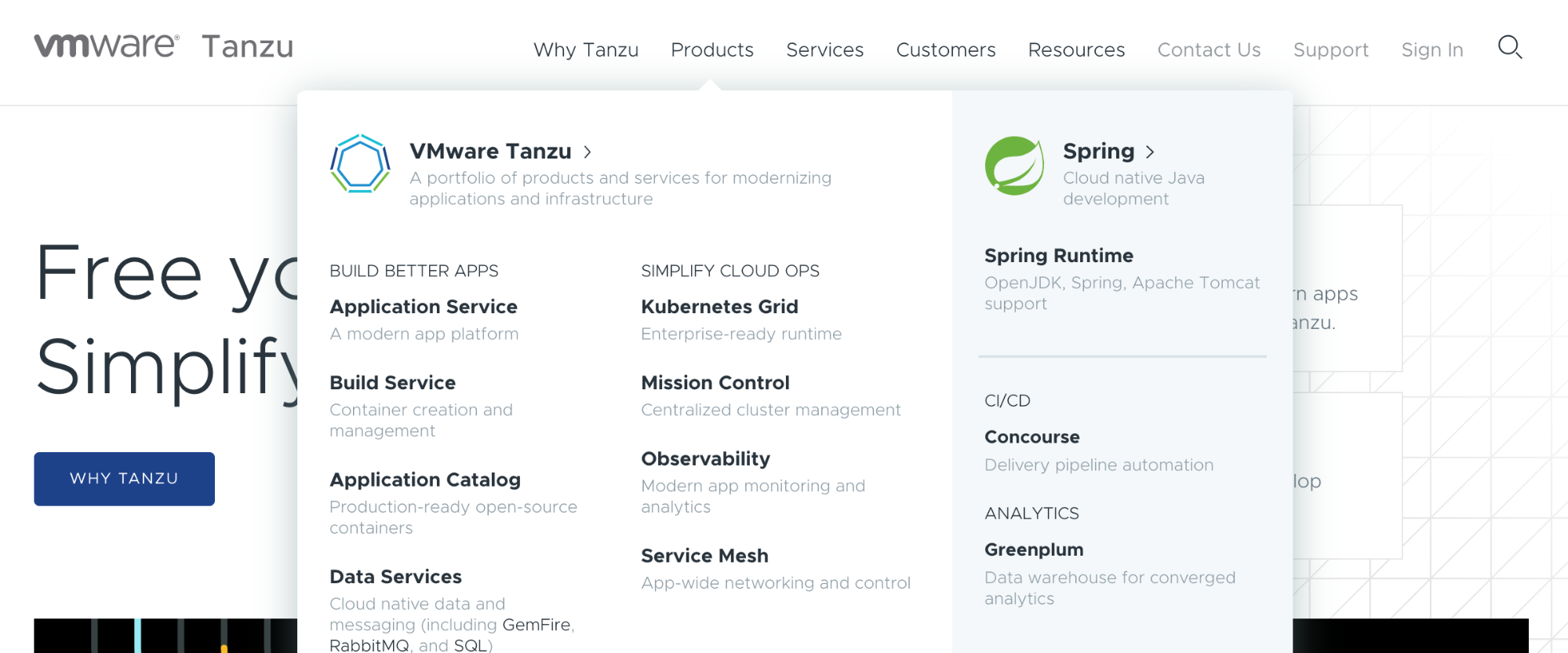

Both Splunk and VMware Tanzu (formerly Pivotal) position individual products in different categories, including emerging ones such as Observability and AIOps, while still marketing in older categories such as SIEM, APM, and CI/CD. This lets them test different positioning and messaging before committing more resources to one or a few key categories.

New Relic similarly hedged their bets until they had enough confidence to go after a single emerging category: Observability. They even changed their product packaging, from 11 offerings to just three, all tied to observability. (Recall that effective positioning involves product decisions as well as marketing.)

Just be careful not to dilute your attention and resources too much when selling and marketing across several categories.

Conclusion

You don’t need to create a new product category to succeed.

Whether you want to reach a successful exit (acquisition or IPO) or just multiply your revenue, both my experience and my analysis of recent tech IPOs shows that the majority of successful companies achieve that without having to create a category.

For those that try, it takes them much more time and resources than anticipated and doesn’t appear to improve the odds of success any more than positioning into an existing or emerging category.

Instead, do what Steve Jobs, Marc Benioff, and 22 of the 25 most recent startups to go public have done: Focus on building something innovative and attracting buyers within an established or emerging category. Let your impact change the category, not your marketing strategy.